University of Southern California

Gender Studies Program Mark Taper Hall of Humanities,

422 3501 Trousdale Parkway

Los Angeles, California 90089-4352 USA

Attention: Professor Alice Echols

Dear

Prof. Echols,

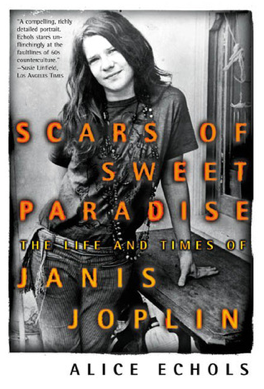

The content of your biography on the

life of Janis Joplin evoked in me a fresh perspective on the historical context

of the blues scene in the 1960’s. While the political and sociological climate

was ripe for radical change and revolutionary thought, the musical climate is

often overlooked or generalized as one big hippie-ridden, LSD-laden Woodstock

festival. Your biography, Scars of Sweet Paradise, The Life and Times of Janis

Joplin, not only examined the life of Joplin, but it presented parallels with the

counterculture of the 1960’s that are so relevant in its effects on the

nation’s current political and social climate. The racial, economic, and gender

divides during the 1960’s played such an influential role in the art and life

of Janis Joplin, which is a major underlying foundation of your biography.

The duality of her persona presented

such inner-conflict, which you examined closely in your book. I

visualized Joplin’s performances and music, but then connected her childhood

background from the early chapters and how that effected her internalization of

her insecurities. You create this sympathy for Joplin in the book, and give readers

such hopes for redemption, success, and happiness for her. However, much to my

own frustration, I never got the impression in your book that she was doomed

from the beginning—such an undertone is nearly impossible to avoid when writing

an account of a notorious tragedy. The self-destructive environment that you

recognized of the blues scene in San Francisco doesn’t present itself as a

foreshadowing to her untimely death. While I knew the story would be an

anti-climatic one with a far from Hollywood ending, I found myself convinced,

over and over, that Janis would end up living until the chapter on her

overdose. Figuratively, she lives on through her music, your book, and the

influence she had on modern day blues and rock.

Janis

Joplin bridges the gap between the early 1960’s folk scene and an electric rock

scene that emerges full-force in the 1970’s. It is that transition that truly

parallels the transition of the politics and societal norms and movements of

that period. The 1960’s were the period of revolutionary thought and action,

and the period of the emergence of Civil Rights, Black Power, Women’s Rights,

and Gay Rights movements truly gain momentum and nation-wide recognition. I was

looking for some more definitive examples of this throughout the book, but

there were mainly brief allusions to them amongst recounts of Joplin’s life.

From

what I interpreted after finishing the book, Janis teetered on the edge of

feminist and anti-feminist, especially in the radical sense of that time. While

she expressed female angst of inequality and mistreatment by men, she didn’t

identify with the feminist movement by any means--“it seems like they haven’t

had a good time in months (306)”—and invaded the male-ridden industry with her

persona, yet that persona maintained a highly eroticized portrayal of her.

Janis was, and was perceived as, a sexualized artist with ambiguous sexual

preferences and public rejection of conventional relationships. This was often

more “Pearl”, her stage persona, than

Janis, which allowed her to maintain a self-destructive character to her fans,

as the miserable blues singer. While this is the publicized perception, your

book truly showed the ways in which Janis was happy, and sought fulfillment in

her relationships and in her actions over the course of her short life.

Apart from it all, it was Janis’ love

affair with music that made her a sensation and a legend, yet an affair with

drugs that caused her untimely demise. This biography showcased the roots of

her inspiration, the world she lived in, and the plight of the counterculture.

Thank you for your thoroughness and dedication to developing such a strong

piece of research that will remain a relevant source for examining the blues

scene and counterculture of the 1960’s.

Warm Regards,

Katie

Montgomery