Following the

Emancipation, freed blacks began to achieve and thrive, much to many white

southerners’ dismay. Ida B. Wells’ interest in the cult of lynching in the

South was stirred by her friend Thomas Moss’ death by lynch mob. He was a

successful grocer that had caused a white grocer’s business profits to decline.

This stirred up strong hatred and envy—Southern whites held a lot of

entitlement to put the black men and women back into the place they were just

years prior. The Ku Klux Klan, along with Jim Crow laws, resulted in a

political agenda that supported the exploitation of free black men and women in

the South. Wells saw lynching as a tool, used by southern whites, to keep freed

black people from gaining back their humanity and hope after decades of

slavery, abuse, and dehumanization.

During slavery in

the United States, white men consistently violated black slave women with

sexual violence and exploitation. It was another component of “ownership”; the

white man had legal right to the slave’s body. Post-emancipation, that exertion

of control was continued, not just by rape but also by the lynching of black

men. It was a way to maintain dominance over the bodies of freedmen—using fear

and intimidation; whites used he-said-she-said finger pointing to justify lynch

mobs. The court systems believed the accusers, as the accusers were white, and

the assailants were black. They justified lynching and accusations with the

notion of the dehumanized, savage black man, pursuing white women. This was

during a time where a woman’s purity and domesticity were the social

expectation; to even hint that a white woman may have voluntarily entertained a

black man’s courtship was scoffed at. Ida B. Wells pointed out the irony in her

publications; that while white men raped and impregnated black slave women,

sometimes falling in love, they couldn’t imagine an instance in which a white

woman would allow that with a black man.

Ida B. Wells’

campaign against lynching contributed to the mobilization and development of an

organized African-American’s women’s movement because the validity and exposure

that she gained through her public rhetoric speaking out against the unjust

lynching practices of the south gave black women a voice. By sharing her

findings of the hundreds of southern lynching deaths, Wells was able to exert

her presence and unite black woman across the nation to begin speaking out for

African-American rights, justice, and equality.

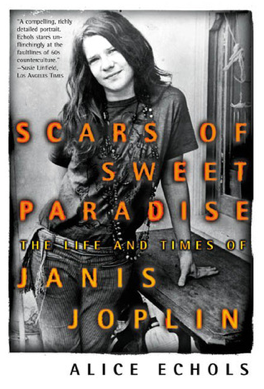

^^ During my reading and search for photos, I found this book. Interesting that this publication would pop up during a search for Ida B. Wells quotes.